The Appalachian Trail doesn’t wait. Neither should you.

Author. Adventurer. Trailblazer.

Joey Shonka, a seasoned long-distance hiker and mountaineer, brings his epic journey on the Appalachian Trail to life in this gripping memoir. Best known for traversing the entire continent of South America on foot, thru-hiking the Andes over three years and immersing himself in diverse cultures and wild landscapes, Shonka started his adventures close to home on North America’s iconic trails.

What Readers Are Saying: With an average rating of 4.0 out of 5 stars from 35 reviews on Amazon and 3.84 stars from 37 ratings on Goodreads, readers praise Shonka’s authentic voice and immersive storytelling. Dive into the adventure that has hikers and armchair explorers alike raving about the trail’s highs and lows.

Click to Expand:

Chapter One: Amicalola Falls

One day, I realized I needed to take a long walk in the mountains. I could feel the desire to detach from society deep within me.

I decided the long walk would be on the Appalachian Trail. This journey stretches from Springer Mountain in the North Georgia Mountains to the summit of Mt. Katahdin in Northern Maine. I hoped to complete a “thru-hike” or to hike the entire distance in one calendar year.

The AT, as the Appalachian Trail is known in hiker circles, was undoubtedly one of the most challenging goals I had ever set. The beginnings of such an adventure are organic, though. I first closed out any pressing affairs I had in the world. I then placed a pack on my back filled with various objects needed to survive while away from civilization and caught a ride to the approach trail.

Day 1: With a forecast calling for late March rains and a preemptive springtime mist hanging over the tops of the evergreen forest, my wife dropped me off at Amicalola Falls State Park. Here we shared a cheerful goodbye. A park ranger then photographed me for inclusion into an album of optimistic thru-hikers. The ranger carefully recorded my information and some identifying characteristics needed in case of a rescue effort.

My dog Jack was along for the hike and carried a pack containing his dog food, dinner bowls, and a dog-sized poncho. The plan was to walk until an illness or a severe injury forced us to stop. While hiking in the mountains, I thought this to be inevitable. I believed I had very little chance of making it all the way to Maine, with so many variables involved beyond my control. But I was still optimistic.

After one last crushing hug and a promise to call soon, Jack and I began our hike by walking underneath a broad stone arch behind the ranger’s station and ascending a wide, well-maintained earthen trail. The sullen skies broke free, and rain fell almost immediately, so I donned an insulated raincoat and secured Jack’s poncho. I stored Jack’s food in waterproof sacks against such a contingency. We were both in high spirits, but as he bounded back and forth, he caused issues. I tied his pack to mine with a rope to keep him close and prevent him from walking up to strangers.

He was a Great Pyrenees with a brutish appearance. Even though he possessed a gentle disposition, he intimidated those who did not know him. After the third or fourth time he nearly tripped me, I realized the situation was not ideal. I also began sweating profusely under the insulated raincoat when the rain stopped. Then I told myself we would only stop hiking at the top of the waterfall. It was my first push.

Soon enough, the route widened to a gravel path with a sweeping fog rolling across the open valley on the left, vapor trails intertwining amongst the points of the dark green canopy. The top-of-the-falls parking lot came into view, a bare hardtop stretch with a water pump and restrooms. I took off Jack’s pack and then dropped my own beside the water pump before allowing myself to gasp for air.

When I went to fill Jack’s bowl with water, he let out a sharp yelp because I stepped on his paw. He forgave me instantly in the casually anonymous manner that all dogs seem to do. I then took a moment to settle my nerves. This was not the auspicious beginning I envisioned while planning this grand adventure.

I previously hiked the Georgia section of the Appalachian Trail with my father and knew what I was initially up against. So I pragmatically told myself I would reevaluate the situation when I arrived at the Georgia and North Carolina border. On with the packs, Jack and I were off, off into the woods, away from civilization, away from the comfortable life I left, away from my beautiful wife.

The rest of the Approach Trail from Amicalola Falls to the first shelter along our journey seemed gently graded, or at least with relatively little elevation gain compared to the first of the day’s miles. Jack slowly learned to walk correctly with the rope binding him to me, and my legs slowly stopped complaining.

The forest lacked much green vegetation, but the bare branches were comforting, as if conveying the truth of myself and the forest being some distance away from a full flush. I arrived at the Black Hawk Shelter to find tents in the surrounding area. The sun was already setting, so I stopped in for the night. The shelter contained only one person.

“Hi, how’s it going?” I called.

“Great, I’m letting my tent dry from the crazy rains last night.”

“Is it cool if my dog crashes in the shelter with us?”

“Sure, I like dogs.”

The hiker was originally from New Hampshire, had just finished serving four years with the Marines in Iraq as a tank mechanic, and smoked Camel cigarettes, which I enjoyed with him after the evening meal. I cooked dinner on a new stove purchased for the hike, a fantastic tool capable of boiling two cups of water in 90 seconds using a titanium cup wrapped in neoprene. The meal was easy; I boiled the water, threw in some couscous, and, after fully hydrated, topped it with a pouch of tuna.

As we sat and talked, I wondered if all the hikers along the journey would be as pleasant and accommodating. Night brought a breathless cold, so I unzipped the sleeping bag to spread it like a quilt over Jack and myself. I had obtained a short foam sleeping pad and a blanket for him, but he was cold and clearly nervous, so I pulled him close and let him use my shoulder as a pillow. Soon he was snoring.

We both slept fitfully, surrounded by unfamiliar sounds and feelings. The night seemed longer than it should have been, and each time I awoke, it was as if I would never fall back asleep.

Day 2: I made pancakes for breakfast and used almost all the water in my containers between cooking and cleaning. The sheltered area’s water source was downhill, nearly a quarter of a mile away, so I walked on with what little water I had remaining rather than hike an additional half mile.

The hiker I shared the shelter with the night prior was ready at the same time as me and asked,

“Do you want to hike together?”

“Sure.”

I was open to anything on the second day of my attempted thru-hike.

The trail leading up to Springer Mountain required a hefty toll of morning effort to climb several switchbacks, where the route would double back on itself to lessen the angle of the elevation gained per foot. To me, it seemed endless, even though I had hiked this section before. We were at the summit and the official Southern Terminus of the Appalachian Trail within the hour.

A grizzled hello from a sturdy thru-hiker alumnus named Many Sleeps welcomed us. He then took down our information and gave me some personal encouragement,

“You’ll make it. It’s always the jovial guys who don’t take it too seriously that do.”

Even though I had doubts, I smiled through my insecurity as we walked on. On the previous father/son hike, I knew but a few miles remained in the journey before going home. It was novel and somewhat disconcerting to gaze toward the top of a mountain and realize it was simply the first of hundreds on the path to reaching the goal.

A hiker named Mountain Squid took down our information again just past the summit in a gravel parking lot. He asked us if we had “trail names” or nicknames to distinguish ourselves during our hike. My companion identified himself as “Yankee” because he was from the north of the United States. I replied with a name I had chosen, “Zion.” To me, Zion meant utopia, and I must admit it was more than a little cheesy.

Yankee, Jack, and I walked on, perhaps mistakenly declining the coffee and donuts kindly offered by the Mountain Squid. The hike was challenging, and the ongoing conversation helped to distract from the aching muscles.

Fatigue seemed a constant companion in these first days. The discussion covered various topics, from our belief structure to our families to our respective mates. We seemed to get on like old friends, and he had a peculiar way of blowing air through his closed lips, which reminded me of my grandfather.

The next shelter appeared late in the afternoon; hikers crowded the platforms and camping spots in the surrounding area. This was the rule rather than the exception early in the hiking season. Such hesitant optimism abounded in this area. A sense of adventure laced with uncertainty in completing but a small fraction of the goal we had set.

This was the beginning of the journey I hoped would bring balance to my life, yet I could not clearly describe what I expected to find.

The shelter area felt like an ancient summer camp, well-packed earth surrounding a structure of aged building timbers with a radius of tree trunks worn smooth from the brushing fingers of a thousand passers-by. Nearby, I set up my camping hammock and the tarp I had brought for Jack to sleep under in case he refused to sleep in the hammock. Then I introduced us to a crowded table.

As the conversation continued, I defended my choice to hike the Approach Trail rather than start at Springer Mountain, the official Southern Terminus. The Appalachian Trail is challenging, and the Approach Trail is one of the more difficult sections at the beginning of the hike. I conceded that the Approach Trail is not technically part of the Appalachian Trail. But had I skipped it, I would not have met Yankee.

After dinner, I laid down in the hammock; with a gentle protest, Jack agreed to sleep with me. The closeness was comforting. We had lain in an almost identical position on the couch at home, his broad head laid across my chest, legs splayed about my ribs, long pink tongue hanging out of the side of his mouth in the manner he always seemed to do when satisfied. Years later, we learned his tongue hung out of his mouth because of a series of minor strokes. He gave no indicator of stroke other than with his tongue, which would slowly dry in the air outside of his mouth, making him pull it in with a wet sucking sound. Yankee also retired to space some distance away from the shelter.

In the early AM, I awoke to a long, high-pitched whistle ending with an explosion, followed by automatic rifle chatter and the shouts of soldiers. The National Guard training facility nearby was engaged in a war game. My last thought before falling back asleep was a bit of sympathy for Yankee. He had just returned from the war in Iraq and was hiking to decompress from the past 4 years of his life in the desert.

How could I possibly understand what he must have felt at that moment?

Day 3: Yankee left a bag with some of his superfluous supplies, such as extra food, batteries, and random bits of gear hanging on the steel bear cable system beside the shelter. He meant this as a gift for other hikers to use as they needed. This stash spot was a clever arrangement of cables and pulleys spanning two tall trees that allowed hikers to easily hang food above the reach of any wildlife.

Yankee had started his hike with 100 lbs of food and equipment in his backpack, not realizing he could buy most of the items he needed for his journey every four or five days. This was a source of great humor for other hikers who had planned more appropriately.

The morning was tough. We hiked up a steep mountain, then down into a gap, another hill, and another gap. Yankee had a map of this section containing a detailed elevation profile, indicating that the rest of Georgia would follow this general trend. When I hiked this section over the previous year, it was during the summer, with light gear and the knowledge the end of the journey was only days away.

The mountains seemed more manageable to climb when I knew I was going home soon afterward. I did not need to hold back, conserve, or hoard strength for the days ahead.

We had lunch beside a burbling creek by the name of Justus. I grunted with weary satisfaction while soaking swollen feet in the cold water and plopped down on a log that straddled the inlet of an expansive pool. Jack lay down beside his pack, panting and heavily spent, even though we still planned to cover more miles before dark.

After lunch, Yankee fell behind to use the bathroom, so as late afternoon approached, I planned to camp for the night when I reached the top of Ramrock Mountain. The small summit was spectacular, a wide vista opening across a deep valley with a shelf of rock to sit and watch the sunset. Maybe it was the fact I was just breaking in my legs and feet or that it was near the end of the day, but I felt incapable of moving up the side of that mountain.

Short switchbacks wove between crumbling gray boulders hung with soft mosses during the ascent. I found a patch of lush green grass just past those boulders and dropped the packs from Jack and myself before laying back in exhaustion. Here I intended to soak up the last rays of the sun.

The sky above was a pure blue, broken only by sporadic cotton clouds hanging low above us in frames of bare tree branches. Jack panted while I twirled my fingers through the green grass, feeling the evening air’s coolness contrasted by the fading sun’s warmth. A small plastic harmonica I had purchased for the trip provided a distraction. As I blew experimentally on the mouthpiece, I had to smile at myself, for I had no idea how to play.

A few minutes later, Yankee hailed me while struggling up the rocky switchbacks.

“I heard your harmonica from the bottom of this climb. I was going to camp there.”

I used two thick trunks for my hammock while Yankee laid a tarp on the grass patch. We were both low on water, but Woody Gap was about a mile away, so we drank lightly during the night. Darkness crept over our space, and the valley beneath us slowly filled with growing shadows. The Earth became quiet.

Late that night, Jack awakened me by heaving most piteously. I scarcely had the time to unzip the tent flap on the side of the hammock before he let loose with a tremendous stream of yellow vomit. After some time had passed, he laid his head back on my chest, and I stroked his ears until we both fell asleep.

Day 4: I should have opened the other side of the hammock during the night; Jack had filled my camp shoes with vomit. Beyond that, I did not have enough water to cook breakfast, so I tossed my gear into my pack and hiked quickly for the gap. We crossed a small stream before the gap, where I rinsed the camp shoes downstream from the trail.

Woody Gap had bear-proof cans to discard our garbage and picnic tables to spread out for breakfast. I also dumped Jack’s sleeping pad because he was not using it, and it interfered with his head’s movement while he walked. Jack looked worn out, perhaps a remnant of the sickness from the previous night.

We then ascended several mountainous hills and arrived at a stream near the base of the biggest obstacle that day, Blood Mountain, 4,461’ in elevation and the highest peak along the Appalachian Trail in Georgia. The shelter at the mountain’s summit was an excellent target for the night, so we carried extra water.

This might not sound like a laborious task, simply having excess water, but a single liter of water weighs 2.2 lbs, and we each carried 4 extra liters. This was an additional 8.8 lbs added to already heavy packs on the most strenuous climb at the end of a trying day.

As we neared the top, soft dirt gave way to slabs of granite slanting upward. At the top, we were the only hikers in for the night, so we claimed space on the single intact bunk shelf and scaled a massive boulder in front of the entrance for a scenic view. Rolling winter-brown hills abounded in all directions. I hugged Jack and wondered if this view felt the same for him or if he felt what I felt when looking out across the slow dreaminess of the South.

Wrapped tightly in a warm sleeping bag with an exhausted Jack on my shoulder made the day seem far away. The wind whispered through the glassless windows of the shelter, bringing with it the final twinges of a retreating winter.

The Civilian Corp of Engineers built this structure less than a century ago with solid local stone set in mortar. It appeared timeless, ancient, as if it had always been there. When I awoke for a call of nature, I watched the moon hanging low above the roof of the building, seeming to lay mere feet above the split wooden shingles and so bright as to drown out the stars.

Day 5: We awoke early and tossed back a hasty breakfast, then started down the mountain toward Neel’s Gap. A store containing an abundance of provisions is located there. We were both low on candy and quick snacks. These were always the first items to run short. Jack was out of dog food as well.

At some points, the descent was incredibly steep, the trail composed of stacked boulders set to act as stairs, and I noted Jack favoring his front paws. The store at the gap was full of hikers and other day-use patrons, a milling commotion compared to the forest. So we stationed ourselves at picnic tables on a stone patio overlooking a broad valley to spread our things out and decide what to send home.

As we debated, the store owner asked Yankee if he needed help determining what to send home. They called this a “shakedown.” My hiking companion had gained some trail celebrity because of his high initial pack weight. Yankee spent a considerable amount of cash in the store. Still, in his defense, the new lightweight equipment he purchased dropped substantial weight from what he was carrying. I bought enough food for the next week and extra snacks to enjoy while we sat and relaxed. Jack & I split an 8oz block of cheese, and his ears perked up, as they always did with human food involved.

He had thick ears, very substantial, very soft. While I daydreamed, I would twirl his ears around in my fingertips. Yankee and I had just packed up for departure when he began rummaging through his pack with some concern.

“I just lost an envelope with like $400 in it.”

“Don’t worry about it; it is here somewhere.”

We continued to search through his belongings. After a half hour, another hiker named Johnny Cash came over to our picnic table.

“Did either of you guys lose an envelope?”

Yankee had left it in the laundry room.

We hiked out in high spirits, reminded of the good people in the world, and walked a few more miles in the fading light before setting up camp in a flat pine-lined gap. Jack lay down as soon as we arrived and rose at dinner time. As we descended the ridge to get water for the night, Yankee asked about my first attempt at writing a book.

I gave the premise of how I felt the world’s good and evil pulling at me constantly, seeking to lead me. But I needed to explain this more adequately in that book instead of crudely mixing fiction with non-fiction and failing miserably. This resulted from a new awareness. I now constantly wondered what life meant, sometimes burning a silent day deep in contemplation.

A relationship was slowly building between myself and an external force in the world whom I dubbed God. However, this name was only what I identified with the positive or guiding energy in the world. The term was insignificant, only the feeling I associated with the name. I was raised Catholic.

One goal for this journey I did not openly share was a more precise definition of this feeling and greater knowledge of what and who I am.

The dark air in the pine glen was crisply cold. Jack spent most of the night tenderly licking the sweat off my bare back and grunting with pleasure, which raised the question if his dog food was providing him with enough sodium. I purchased moisturizing treatment for his foot pads in Neel’s Gap, but he licked it off as quickly as I could apply it. In his defense, it did smell delicious, and I was tempted to try it.

This was a night that I could appreciate his warmth, even if he did snort and snore.

Day 6: Jack was stiff when we awoke the following morning and seemed unable to move correctly. He did not bend his knees while he walked, instead stumbling forward in an oddly jerking fashion. I was stiff too, but I assumed that we would both loosen up after we began moving.

The day went by slowly, up one mountain, down into the following gap, miles unhurriedly ticking by. Georgia does have several gorgeous open views along the Appalachian Trail. This day we trudged through the pre-spring barrenness of winter, keeping our conversation flowing, giving each other advice on our respective lives, and trying to calculate when we would finish.

That was quite ridiculous because we had only hiked about 50 miles. But we constantly set goals for the following day, week, or month.

Isolation makes fast friendships on the trail. We already knew much about each other, and I liked Yankee. Before lunch, we left the trail to cross into a valley that held the Low Gap Shelter. The shelter floor was high, and Jack could not leap to lie in the shade. He stumbled to the back of the structure before collapsing when I lifted him gently inside.

I followed his example after drinking some fresh water from the shallow stream that babbled over smooth black stone just past the entrance to the shelter area. As I lay in the shade, pillowed snuggly against Jack’s ribs, I decided I felt good about our progress. We were covering miles, sore but happy, almost elated with these breaks. I had already made an interesting new friend. I was also in a considerably peaceful mood. This was my first experience with surging endorphins after 12 hours of daily cardio. It was like a narcotic.

We packed up after a long lunch break, and Yankee left while I tried to put Jack’s pack onto his back. He refused and clearly did not want to carry the load. I then tried to call him over curtly, and he simply stared straight into my eyes so there would be no confusion regarding what he wanted.

Then I ruffled his ears softly and spoke encouragingly, slowly moving his pack toward him and asking him to put it on. He refused, so I hung his load over my own and returned to the trail. The other hikers in the shelter laughed, but they might not have understood.

Jack was here through my choosing and not his own; I would not make him carry his pack. We caught up with Yankee soon after this. The dog pack swung erratically back and forth and threw off my balance. Yankee and I discussed this situation when Jack showed signs that he could not maintain a hiking pace.

“Well, I will put it on him after he gets warmed up.”

We continued walking up and over hills, through valleys, and past young-budded forests on the cusp of bursting into spring. When I tried to put Jack’s pack back on, he balked but allowed me to secure the straps under his stomach. Then he began hobbling, clearly unable to carry his pack, presenting me with a tough decision regarding his deteriorating condition.

So I called my wife to have her pick up Jack at the Unicoi Gap, which was about two hours from our apartment. I also dumped Jack’s food out and stowed his empty pack in mine, so I would not have to counter its inertia.

“Alright, Yankee, I’ll truck it to make this meeting. Do you want me to pick up anything for you in town?”

“Yeah, will you get me a pack of cigarettes and a soda, too?”

I smiled. My companion had repeatedly mentioned that he would quit when his smokes ran out. I’m the same way. I both love and hate to smoke.

After this, I turned and herded Jack along the trail ahead. Yankee and I had determined from the map that a bald mountaintop about a mile past the Gap was well-suited to camp for the night. From then on, Jack seemed to perk up, almost as if he knew what was happening. We walked more rapidly, and he required no encouragement to keep on the trail.

I felt a sharp sadness, perhaps a twinge of regret, but I also realized there was no way I could carry my food and his. We were both large animals and consumed substantial quantities of food. He was going to have to go home.

We stopped for water near a shelter on the top of Blue Mountain before starting a two-mile descent into the Unicoi Gap. My wife arrived with another dog in the car close to dark. I then learned she had assumed Jack was not coming home for a while and had already adopted a puppy named Pasha.

Pasha and Jack got along well. We drove into the mountain town of Helen, where I purchased some tape, bits of food, and Yankee’s requests. When she dropped me off in the dark, I told her I loved her, but as I watched her and the dogs drive away, I felt that same twinge of regret when thinking about Jack going home. I did not know when I would see them again.

Another mountain named Rocky was a dark mass in front of the path. I paused to fill a water bladder at a stream near the base of the ascent. Once my footsteps stopped filling the space in the air, I felt the forest pulse in the night and realized I now walked entirely alone for the first time. I felt a shudder, a stab of premonition, almost like something in the dark was watching me.

Would Yankee walk through the night to catch up? As I listened to the stream’s murmuring, I decided he might not be coming. Two suitable trunks provided support for the hammock on a slope. I then hung my food bag high in the trees. I did not need a nighttime bear encounter, my first night alone.

As I lay back in my hammock with legs protesting from the workout I had given them throughout the day, I contemplated the following morning. How motivated would I be without Yankee and Jack? I planned to walk as far as my legs would carry me. Yankee would catch up when he could.

This resolve weakened me, and I felt lonely, absent-mindedly listening to the stream and swinging my knees from side to side within the hammock to rock back and forth. Each noise seemed unduly amplified and cause for worry. Seeing a headlamp bobbing in the darkness brought me out of my daze.

“I didn’t think you would catch up in the dark!”

“I told you I would, bro. Thanks for the smokes and the soda you stashed by the road for me. Want some cash?”

That night we reached the grassy bald spot I remembered passing on my last hike through Georgia. Hiking in the dark that night was strenuous as this was the first time either of us had attempted to walk over 15 miles, but at the top, we were rewarded with a great camp. Here we spread our sleeping bags out on an unoccupied flat area. The wind had picked up, so I zipped the sleeping bag hood around my ears and lay back, gazing at the stars.

Day 7: We tackled two extended climbs, Tray Mountain and Kelly Knob. The switchbacks leading up to Tray felt repetitive. Although they added total distance, the incline was not as great, and the increased pace we could maintain mitigated the time added by the extra length.

After the summit of Tray, the trail rewarded us with a short section of reasonably flat walking.

I now appreciated just how easy it was to hike without Jack. Jack had not wanted to walk, at least not in the capacity I did. He liked to sniff and pee on everything. So I told myself I had made the right decision in sending him home, but I still missed him terribly. I would catch myself unconsciously looking for him, feeling like I had lost something important.

An old foam cooler greeted us at a low point in the ridge named Addis Gap. Black marker letters on the outside informed us the sodas and candy inside were compliments of a man named Preacher Dude. Preacher Dude camped in and around the Deep Gap Shelter. He made written promises of free eggs and breakfast items, quickly settling our debate about where to sleep that night.

The climb from Addis Gap to the top of Kelly Knob was ruthless. As we hiked, the trail turned so that a point high in the distance would appear to be the summit, but when we reached that point, the course would turn again to present a more ascending trail, creating one false summit after another. The subject of Preacher Dude dominated the conversation.

He had introduced us to a commonality along the Appalachian Trail known as trail magic. An act of kindness or provision given to a hiker is known as trail magic. The person giving is known as a trail angel. I liked the concept and resolved to become a trail angel one day.

We had enjoyed a candy bar and a cold drink on a hot day before the most arduous climb to date on the AT. This was a moment of respite for which we were both grateful. At any other time, this might have felt like a small gesture. But ordinary things gain great value when away from everything familiar.

The journey down from Kelly Knob seemed easy after such a monumental climb. Before long, we reached a side trail leading to the Deep Gap Shelter. The side trail was 0.3 miles long, and I balked. We would walk an extra 0.6 miles round-trip to meet the Preacher Dude. These tenths would add up as I now measured my days not in time but in hard-won miles.

Still, we slowly moved to the shelter and passed a spring along the spiraling trail into Deep Gap. Here we found several cans of sodas in the cold water. An assortment of hikers standing around a smoky, sputtering fire pit to the side of the shelter greeted us. This shelter was nearly enclosed, with a raised porch, bunks, and glass windows. It was a far cry from the three-sided lean-to shelters of past miles.

We introduced ourselves and learned the Preacher Dude was not there; he was fishing, hoping to cook the shelter guests a trout dinner. Screen-walled tents filled various locations around the shelter area. The most interesting one enclosed a picnic table covered in food and a set of propane burners supporting a pot of bubbling stew. There was also a donation plate with several bills and coins on the picnic table.

Here we ate our fill and decided to sleep under the stars again. This cowboy camping made for a fast morning. The Preacher Dude returned later that night.

“Yeah, I am not like most preachers,” he said. “I like to smoke my pipe, and I even occasionally bring some cold beers for you guys. Yeah, I am not like most preachers.”

He chuckled, pleased with himself.

“So why do you do all this?” I asked.

He provided the trail magic to hikers without help from others. We previously assumed this was the operation of a church or, at the least, a group of dedicated people. Heavy gear was involved, almost too much for one guy to carry.

“It’s my ministry,” he replied simply. “You guys don’t get the nutrition you need out here, and I can at least give you a couple good meals before you go. I love hikers.”

“So, have you ever hiked on the Appalachian Trail?”

“Bits and pieces. Mostly in Georgia.”

Preacher Dude was a man of concise sentiments and pleasant humor, so I left the conversation at that.

Day 8: The smell of fresh coffee brewing rousted us from our sleeping bags quite early. The Preacher was up at dawn and tailored our breakfast to our tastes. He fried my eggs in a clean pan with olive oil, green peppers, and onions. He fried Yankee’s eggs in bacon grease. Even after years as a pescatarian, I still missed bacon. That salty, fatty, crunchy goodness.

The delicious fresh coffee kept going around, and an enormous pot of oatmeal appeared. The Preacher even provided bagels, apples, bananas, and assorted snacks. This seemed like a feast of extraordinary proportions compared to what breakfast typically looked like. I felt full for the first time in a week.

The walk from the Deep Gap Shelter to Hiawassee Gap was without significant incline or decline, a welcome change for two hikers packing full stomachs. We pushed for the border of Georgia and North Carolina that night to camp in the second state along the Appalachian Trail. A cooler full of sodas from a hotel in Hiawassee met us at the next road crossing. I had plans to camp for at least a month, and Yankee shared my sentiment, so we enjoyed the sodas with quiet thanks.

Then we cruised smoothly over gentle hills with rolling momentum, only low rises in the path ahead, before long reaching midday. An offshoot trail for a shelter appeared, but we decided not to visit. During this journey, we would walk 2,175 or 2,182 miles when including the Approach Trail but shied away from a few tenths of a mile off-trail. Every debate on the trail ended the same, with someone decisively saying those side miles did not count.

At this stage of the trip, we were constantly passing or being passed by other hikers, both south and northbound. On this day, we met a pair I knew were exceptional, even though I did not know why. Named Bemis and Softball, thin and lanky, with tanned arms and matching full beards. They both had firm handshakes with solid eye contact. How much those two simple indicators will show about a person is incredible.

“So, how long have you guys been out?”

This was a standard greeting.

“Nine months,” Bemis replied. “We started in Maine.”

At this point, I could not comprehend what they must have felt, so close to completion. They had set the goal to hike through all 4 seasons on the AT and had done just that. Ice axes and all. We shook hands respectfully and congratulated them before parting ways.

“Dude, did you feel that?” Yankee asked.

“What do you mean?”

“The feeling coming off of those guys. They were calm and chill, almost like they had some weird trail aura. Do you think we will get like that?”

I had felt it too. The two SoBos or South-Bounders just felt different. Something about the look in their eyes, their easy stance countering the weight on their backs, the thick weathered beards.

This spring day became unreasonably hot, as they often do in the North Georgia Mountains. With sweat-soaked bodies, we lunched under the shade of pines on a cushion of soft needles for a few hours. A new hiker joined us while we waited until mid-afternoon for the heat to fade.

Crossing the border into North Carolina felt different, more natural, different in the same way Bemis and Softball had felt. I had never walked past Bly Gap, a clearing 0.3 miles past the border. There was a hill I had never climbed. I felt excited that I was about to cross into unknown territory.

After photos, smiles, and a round of hearty handshakes at the border, we moved on to Bly Gap. The evening was fast approaching while we filled our water containers from a spring flowing past the trail before climbing up my unknown hill. It was only about 40 feet high, so about a minute later, we were on the top.

I can’t believe I had been there twice yet never climbed this hill. The trail looped back upon itself and past a gnarled tree, whose warped branches seemed to welcome us to the next stage of our journey. After the hill and the tree, wooden steps built into the trail’s surface seemed to stretch on and up indefinitely. Chilled sweat had soaked me when we reached the apogee of the stairs.

A quick descent led to a relatively flat area where we made camp. The third addition to our party did not carry a stove. He instead started a fire to cook his meal, which turned out to be quite welcome in the surrounding darkness. We stood huddling around the fire after dinner when he noticed something nearby.

“Hey, is that a pot plant?”

“No, I don’t think so,” I said. “The leaves are wrong.”

“Yeah, check this out.” The other hiker pulled out a quart-sized plastic bag stuffed with seeds.

“I’m going to plant the whole AT with pot, man.”

“I’ve got it,” I said, “Your trail name needs to be Johnny Appleseed.”

He agreed wholeheartedly, and we spent the rest of the evening around the fire.

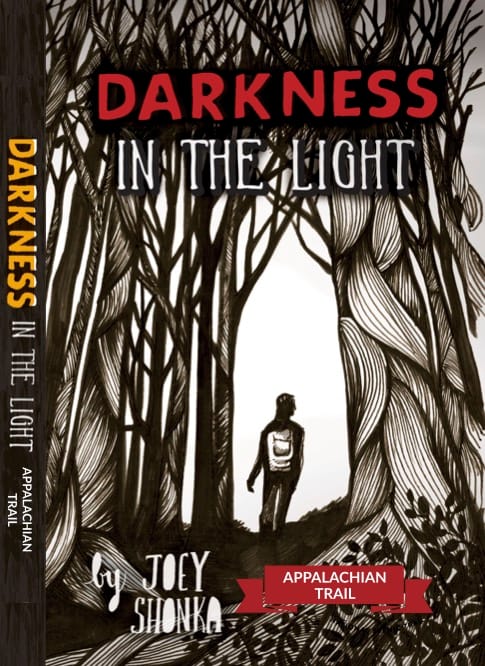

The Appalachian Trail: Darkness in the Light

The first book in The Triple Crown of Trails Series, chronicling an unforgettable thru-hike along one of America’s most legendary paths. Adventures from Georgia to Maine along the Appalachian Trail! Join Joey as he navigates rugged terrain, encounters fellow hikers, and uncovers the raw beauty and challenges of this 2,190-mile journey. From misty mountains and dense forests to moments of solitude and triumph, this book captures the darkness and light of the human spirit on the trail—balancing hardship with inspiration, danger with discovery. Part of a series that explores North America’s Triple Crown of Hiking, including the Pacific Crest Trail in “An American Nomad” and the Continental Divide Trail in “A Strong West Wind.” If you loved the immersion of “The Caminante,” Shonka’s South American odyssey, you’ll be captivated by this intimate look at the Appalachian Trail’s transformative power.

(Available in four formats including audiobook—begin the trail today for instant inspiration!)

Joey Shonka

Author

Meet the Trailblazer!

Joey Shonka is a storyteller who has traveled the world in pursuit of adventures, long-distance hikes, and mountaineering. One of his life’s highlights is walking across the entire continent of South America, thru-hiking the Andes—three years, six amazing countries, and a complete immersion into cultures, traditions, politics, cuisine, and wild natural spaces.

A University of Georgia alumnus (BS ’05 in Biochemistry), Shonka has also conquered the Triple Crown of Hiking in the U.S., completing the Appalachian, Pacific Crest, and Continental Divide Trails.

His experiences as a biochemist and explorer fuel his vivid writing, blending scientific curiosity with the thrill of the outdoors.

The Trail doesn’t wait. Neither should you.

Whether you’re chasing sunrises over Springer Mountain or just craving a story that stirs the soul, Darkness in the Light delivers the rush. Taste the Adventure!

Step into the unknown. Your path starts here.